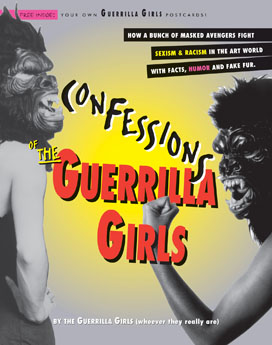

An interview from our first book, Confessions of the Guerrilla Girls, published in 1995. For a more recent Q and A, please see our FAQs.

Rosalba Carriera: When we first spoke to the press, it was clear we needed code names to distinguish between members of the group. The day we taped NPR's Fresh Air, Georgia O'Keeffe died. It was then that it came came to us to use names of dead women artists and writers to reinforce their presence in history and to solve our interview problems. It was as though Georgia was speaking to us from the grave. So far, Frida Kahlo, Alma Thomas, Rosalba Carriera, Lee Krasner, Eva Hesse, Emily Carr, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Romaine Brooks, Alice Neel and Ana Mendieta are but a few of the famous women from history who have joined us. We are actively recruiting Rosa Bonheur, Angelica Kauffmann and Sofonisba Anguisolla. (Of course, one Girl didn't care for the idea and calls herself GG1.)

Q. How did the Guerrilla Girls start?

Kathe Kollwitz: In 1984, The Museum of Modern Art in New York opened an exhibition titled An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture. It was supposed to be an up-to-the minute summary of the most significant contemporary art in the world. Out of 169 artists, only 13 were women. All the artists were white, either from Europe or the US. That was bad enough, but the curator, Kynaston McShine, said any artist who wasn't in the show should rethink “his” career. And that really annoyed a lot of artists because obviously the guy was completely prejudiced. Women demonstrated in front of the museum with the usual placards and picket line. Some of us who attended were irritated that we didn't make any impression on passersby.

Meta Fuller: We began to ask ourselves some questions. Why did women and artists of color do better in the 1970's than in the 80's? Was there a backlash in the art world? Who was responsible? What could be done about it?

Q.What did you do?

Frida Kahlo: We decided to find out how bad it was. After about 5 minutes of research we found that it was worse than we thought: the most influential galleries and museums exhibited almost no women artists. When we showed the figures around, some said it was an issue of quality, not prejudice. Others admitted there was discrimination, but considered the situation hopeless. Everyone in positions of power curators, critics, collectors, the artists themselves passed the buck. The artists blamed the dealers, the dealers blamed the collectors, the collectors blamed the critics, and so on. We decided to embarrass each group by showing their records in public. Those were the first posters we put up in the streets of SoHo in New York .

Q. Why are you anonymous?

GG1: The art world is a very small place. Of course, we were afraid that if we blew the whistle on some of its most powerful people, we could kiss off our art careers. But mainly, we wanted the focus to be on the issues, not on our personalities or our own work.

Lee Krasner: We joined a long tradition of (mostly male) masked avengers like Robin Hood, Batman, The Lone Ranger, and Wonder Woman.

Q. Why do you call yourselves 'girls?' Doesn't that upset a lot of feminists?

Gertrude Stein: Yeah. We wanted to be shocking. We wanted people to be upset.

Frida Kahlo: Calling a grown woman a girl can imply she's not complete, mature, or grown-up. But we decided to reclaim the word “girl”, so it couldn't be used against us. Gay activists did the same thing with the epithet “queer.”

Q. Why are you Guerrillas?

Georgia O'Keeffe: We wanted to play with the fear of guerrilla warfare, to make people afraid of who we might be and where we would strike next. Besides, “guerrilla” sounds so good with “girl.”

Q. Isn't calling yourselves the Conscience of the Art World a little pretentious?

Eva Hesse: Of course. Everyone knows artists are pretentious!

GG 1: Anyway, the art world needs to examine itself, to be more self-critical. Every profession needs a conscience!

Q. Why the gorilla masks?

Kathe Kollwitz: We were Guerrillas before we were Gorillas. From the beginning the press wanted publicity photos. We needed a disguise. No one remembers, for sure, how we got our fur, but one story is that at an early meeting, an original girl, a bad speller, wrote 'Gorilla' instead of 'Guerrilla.' It was an enlightened mistake. It gave us our “mask-ulinity.”

Q. What about the short skirts, high heels and fishnet stockings?

Emily Carr: Wearing those clothes with a gorilla mask confounds the stereotype of female sexiness.

Meta Fuller: Actually, we wear mostly nondescript, black clotheslike every one else in the art world. Sometimes we do wear high heels and short skirts. And that's what people remember.

Q. Why do you use humor? What does it do for your message?

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Our situation as women and artists of color in the art world was so pathetic, all we could do was make fun of it. It felt so good to ridicule and belittle a system that excluded us. There was also that stale idea that feminists don't have a sense of humor.

Eva Hesse: Actually, our first posters weren't funny at all, just smart-assed. But we found out quickly that humor gets people involved. It's an effective weapon.

Q. Do you allow men to join?

Frida Kahlo: We'd love to be inclusive, but it's not easy to find men willing to work without getting paid or getting credit for it.

Kathe Kollwitz : Seriously, we have lots of male supporters and lots of men have asked to join. We're thinking about it.

Q. What was the response to your earliest actions?

Anais Nin: There was skepticism, shock, rage, and lots of talk. It was the Reagan 80's and everyone was crazed to succeed, nobody wanted to be perceived as a complainer. Hardly any artists had the guts to attack the sacred cows. We were immediately THE topic at dinner parties, openings, even on the street. Who were these women? How do they dare say that? And what do their facts say about the art world? Women artists loved us, almost everyone else hated us, and none of them could stop talking about us.

Q. What have you done since then?

GG1: One poster led to another, and we have done more than sixty examining different aspects of sexism and racism in our culture at large, not just the art world. We've received thousands of requests for them and they've found their way all over the world. Museums and libraries have collected entire portfolios. We've spoken to large audiences at museums and schools on four continents, sometimes at the invitation of institutions and individuals we have attacked.

Q. You sound surprised by your success. What did you expect?

Romaine Brooks: We didn't expect anything. We just wanted to have a little fun with our adversaries and to vent a little rage. But we also wanted to make feminism (that “f” word,) fashionable again, with new tactics and strategies. It was really a surprise when so many people identified with us and felt we spoke for their collective anger. We didn't have the wildest notion that women in Japan, Brazil, Europe and even Bali, would be interested in what we were doing.

Q. What have you done besides posters?

Eva Hesse: The posters are our most public communication but we've done other things, too, like billboards, bus ads, magazine spreads, protest actions, letter-writing campaigns. We're particularly proud of having put up broad sheets in bathrooms of major museums.

Rosalba Carriera: We send secret letters to egregious offenders, often honoring them with bogus awards. We gave John Russell of The New York Times an award for The Most Patronizing Art Review of 1986, when he reviewed Dorothy Dehner's show and called her “Mrs. David Smith,” referring to her famous sculptor husband (they had been divorced for years).

Alice Neel: The Norman Mailer Award for Sensitivity to Issues of Gender Equality went to painter Frank Stella when he said he liked the “muscular” work of “girl” artists like Helen Frankenthaler. We shook a hairy finger at art market superstar Brice Marden when he said in Vanity Fair that he wasn't sure if it was good for him to be represented by a female dealer.

Tina Modotti: We sent The Apologist of the Year Award to a woman critic, Kim Levin, for reviewing a show of David Salle without dealing with his misogynist imagery. (Recently, on a panel in Berlin, she claimed to be grateful for the criticism.)

Gertrude Stein: We send Seasons Greetings to friend and foe. We remind the latter that “>We know who's been naughty or nice.” We wish the former “Peace on Earth. Goodwill toward women.”

Frida Kahlo: The next time art critic Michael Kimmelman pans a show that actually includes a fair number of women and artists of color like his hysterical rant against the Whitney Biennial of 1993 we're going to send him a year's supply of Midol.

Q. Have you ever been accused of discrimination yourselves?

Alma Thomas: Yes. Menopausal women felt we were making fun of them by titling our newsletter, Hot Flashes from the Guerrilla Girls. I guess they didn't know the Girl who named it was having them herself.

Kathe Kollwitz: One male journalist is still threatening to sue us for charging white males a higher subscription rate to Hot Flashes than women or artists of color. We thought it was fair, because white men earn more. We told him to go sue hairdressers who charge women more for a haircut.

Romaine Brooks: We also heard from a gay white male, who was angry about having to pay the same as straight white males. So we refined our language to read, “Straight white males with superior earning power: $12., Everyone else: $9.”

Q. Is there anything you'd like to apologize for?

Anais Nin: Our spelling mistakes.

Q. How many are you?

Lee Krasner: We don't have any idea. We secretly suspect that all women are born Guerrilla Girls. It's just a question of helping them discover it. For sure, thousands; probably, hundreds of thousands; maybe, millions.

Q. How do you work?

Alice Neel: Over the past 10 years, we've come to resemble a large, crazy, but caring dysfunctional family. We argue, shout, whine, complain, change our minds and continually threaten to quit if we don't get our way. We work the phone lines between meetings to understand our differing positions. We rarely vote and proceed by consensus most of the time. Some drop out of the group, but eventually most of us come back, after days, months and sometimes years. The Christmas parties and reunions are terrific. We care a lot about each other, even if we don't see things the same way. Everyone has a poster she really hates and a poster she really loves. We agree that we can disagree. Maybe that's democracy.

Q. Where do you get your information?

Violette LeDuc: We usually just count in galleries, in museums, in the media.

Eva Hesse: One of our best sources is the magazine Art in America, which publishes an Annual Guide, where galleries and museums proudly announce their “discriminating” line-ups for the year.

Alice Neel: Lots of institutions provide public information that we reinterpret. That's how we did our exhibition about the Whitney Museum's pathetic record of not showing women and artists of color.

GG 1: For the second issue of Hot Flashes, we wrote a phony letter from an imaginary graduate student asking P.R. departments of 150 museums what was happening.

Romaine Brooks: For the first issue, we sat for days in the New York Public Library, reading everything The New York Times wrote about art during 1991-2. Then, we got personal dirt on the critics from confidential sources all over town.

Ana Mendieta: We're a large, powerful anonymous group and that means that we could be anyone, anywhere like Leo Castelli's proctologist, Mary Boone's plastic surgeon, David Salle's hairstylist, or Carl Andre's next girlfriend.

Q. How often do you meet?

Tina Modotti: Every 28 days.

Q. Who finances you?

Georgia O'Keeffe: In the beginning, we paid for the posters out of our own pocketbooks. And we received unsolicited contributions like one from a secretary at a N.Y.C. museum who wrote, “I work for a curator you named on one of your posters. You're right, he's an asshole. Here's $25.” We sometimes get contributions from women artists when their careers take off. But we have no matron of the arts who writes us big checks, or a Guerrilla Girls' PAC. We do accept retributions from institutions we have attacked when they buy our posters and pay our lecture fees.

Q. What's the ethnic make-up of the Girls?

Gertrude Stein: Our membership is a secret, but the percentage of women of color is better than the general population.

Q. Has anyone said your masks are racist, that they conjure up images of lower forms of jungle life that have been used to humiliate black people?

Zora Neale Hurston: We've talked about that. We are exploding stereotypes here, like when we use the word “Girl.”.

Meta Fuller: There is nothing second-rate or inferior about gorillas and to think so is Homo-Sapiens-centric.

Alma Thomas: I would have preferred pink ski masks.

Q. You've also done posters about abortion rights, the Gulf War, the homeless, rape, Clarence Thomas and other issues that have nothing to do with the art world. Why?

Paula Modersohn-Becker: We consider ourselves inhabitants of many worlds and can appear in any one we wish.

Liubov Popova: We wanted to try out what we had learned about making effective posters in a larger arena.

Kathe Kollwitz: We're not systematic in our attacks. It happens in a much less orchestrated way. Members bring issues and ideas to the group and we try to shape them into effective posters. Sometimes we're all interested in an issue and we can't figure out or agree on how to make it into a poster, so we table it for a later meeting.

Emily Carr: Lots of issues are important to us. We focus on the world for awhile, go back to the art world and come back out again.

Ana Mendieta: An event like the Gulf War, which outraged us, can precipitate a whole bunch of posters in a very short time.

Q. How does an artist “make it”?

Romaine Brooks: Even without discrimination, it is very hard to succeed as an artist.

Alma Thomas: You work in your studio, then take your art around to galleries, which act as agents for a small number of artists and sell their art. Sometimes galleries are approached by hundreds of hopeful artists a week. You also try to get museum curators interested in your work. Museums are public, not-for-profit institutions that buy and exhibit art. They are influenced by what the galleries show and visa versa. Museums exhibit even fewer artists than galleries. Critics fuel the process by judging your work. It is a challenge to get their attention, because there are many more shows than reviews. Art collectors buy from galleries and also sit on the boards and committees at museums, advising them (and being advised by them) on what to collect. To make a living from her art, an artist has to crack this system.

Diane Arbus: Museums and galleries tend to exhibit the same few artists, who are overwhelmingly white and male.

Q. But, isn't judging art an issue of quality? If women and artists of color were really good, wouldn't they make it on their own?

Lee Krasner: The world of High Art, the kind that gets into museums and history books, is run by a very small group of people. Our posters have proved over and over again that these people, no matter how smart or good-intentioned, have been biased against women and artists of color.

Romaine Brooks: Success in art is a matter of luck and timing as well as being good or having talent. Why do white men seem to have all the luck? It's not just a happy accident. Thus far, and throughout history, the system has been set up to support and promote the work of white male artists. That is their luck. In the old days of Western culture, it was patronage and the atelier system. It's not that different now, though patronage doesn't come in the form of royal courts and the Roman Catholic Church, but in the form of gallery owners, collectors, critics and museums who back certain artists. Once enough money has been invested in a certain artist, everyone mobilizes to keep that artist's name out front and consequently in history. The artists who make it in this way begin to define quality.

Alma Thomas: “Quality” has always been used to keep women and artists of color out.

Q. Is art by women and artists of color different from art by white men?

Alice Neel: If art is the expression of experience and everyone admits that gender and race affect experience, then it stands to reason that their work could be different.

Ana Mendieta: That's another thing that we're fighting for. We think the art that's in the museums and galleries should tell the whole story of our cultureour real culturenot just the white male part.

Q. Is the art world like the rest of society in its treatment of women and artists of color, or is it a special case?

Rosalba Carriera: Many people believe that art is special and exempt from conventional scrutiny. While art may be transcendent, the art world should be subject to the same standards as anywhere else. We think there's a civil rights issue here.

Zora Neale Hurston: Women and men of color have been denied equal access to becoming artists in our culture for centuries. But there have been many stunning exceptions and even they are neglected by museums and written out of history books!

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Janson's History of Art, the most widely-used textbook, didn't mention a single woman artist until Janson died. Then, his son revised it, including a big 19 out of 2,300.

Gertrude Stein: There's a popular misconception that the world of High Art is ahead of mass culture but everything in our research shows that, instead of being avant garde, it's derriere. Look at our poster that compares the number of women in jobs traditionally held by men to the number of women showing in major art galleries(Bus companies are more enlightened than NYC art galleries.) The art world is a lot more macho than the post office.

Q. So you can't just stay in your studios, work really hard and hope that you'll get noticed?

Meta Fuller: Of course not. Any veteran of the Civil Rights, Women's, or Gay Rights movement knows that progress is the result of pressure, protest and struggle.

Q. Do you really want to rewrite art history and cancel out all the white male artists we know and love?

Georgia O'Keeffe: Yes and no. History isn't a fixed, static thing. It always needs adjustments and revisions. The tendency to reduce the art of an era to a few “geniuses” and their masterpieces is myopic. It has been a huge mistake. There are many, many significant artists. We're not going to forget Rembrandt and Michelangelo. We just want to move them over to make room for the rest of us!

Q. Hilton Kramer called you “Quota Queens.” Do you really think that all shows must be 50% women and artists of color?

Zora Neale Hurston: We've never, ever mentioned quotas. We've never attacked an institution for not showing 50% women and artists of color. But we have humiliated them for showing less than 10%.

Georgia O'Keeffe: To make up for what's happened so far in art history, every show should be 99% women and artists of color, but only for the next 400 years.

Q. You hate the language that's used to describe art. What's wrong with words like masterpiece, seminal and genius?

Frida Kahlo: If a masterpiece can only be made by a master and a master is defined as “a man having control or authority,” you can see what we're up against. Considering the history of slavery, we suggest changing the words to massa' and massa's piece.

Lee Krasner: Seminal, an adjective for semen is completely overused to describe creative achievement and originality. Yuk. Just thinking about it brings a bad taste to my mouth.

Tina Modotti: Next time anyone feels the urge to use the word seminal, try germinal instead.

Anais Nin: The word genius is related to the Latin word for testicles. Maybe that explains why it's so rarely used to describe a woman.

Q. If the art world is so corrupt and disgusting, why do you want to be part of it?

Kathe Kollwitz: We don't all want a piece of the pie. We are a diverse group, different ages, different races, different sexual orientations and different levels of art world success. Some of us want to blow up SoHo, some have already had museum retrospectives. What we do agree on unanimously is that women and artists of color deserve a piece of the pie and shouldn't be prevented from getting a big piece, if that's what they're after.

Violette LeDuc: People who attack us for wanting a piece of the pie usually have most of it. They wouldn't attack a woman in another field like a law graduate who wants to be a partner in a firm, or a Supreme Court Judge.

Q. What's your position on pornography?

Anais Nin: We plan to have a position on it as soon as we can agree on what it is.

Q. What about censorship? Should museums show obscene and offensive art?

Rosalba Carriera: Sure, as long as some of it is made by women and artists of color.

Q. What about lesbian and gay issues?

Romaine Brooks: We support lesbian and gay rights and some of us are queer.

Gertrude Stein: We've covered lesbian and gay issues in a number of posters. For example,we called for the Far Right to undergo psychoanalysis to determine the source of its interest in Robert Mapplethorpe.

Violette LeDuc: We proclaimed that Clarence Thomas would extend the same right to privacy he demanded for himself to homosexuals.

Alice Neel: We ridiculed homophobic AIDS paranoia in our explanation of Natural Law.

Vanessa Bell: The first Hot Flashes poked fun at The New York Times' puritanical language when covering lesbian and gay issues.

Georgia O'Keeffe: We would like to see art about lesbian sexuality taken as seriously as art about gay male sexuality. And it's happening.

Q. Doesn't the mask keep you from taking responsibility for the charges you make? Isn't that cowardly?

Rosalba Carriera: Actually, what started off as a lark, as a way of doing something constructive with our anger, has become a big responsibility to a huge audience. We didn't ask for it but we're trying to live up to it. None of us has ever profited from being a Girl.

Ana Mendieta: Give us a break. Was the Lone Ranger a coward?

Q. Has anyone ever tried to expose who you really are?

Paula Modersohn-Becker: One guy threatened us. But the thought of millions of angry, spear-carrying feminists on his case was more than he could bear.

Liubov Popova: A number of years ago, two guys put up a poster with their photos, claiming to be the Guerrilla Girls. Some weird career strategy!

Q. Have you made a difference?

Emily Carr: We've made dealers, curators, critics and collectors accountable. And things have actually gotten better for women and artists of color. With lots of backsliding.

Frida Kahlo: Just last year, Robert Hughes, who in the mid-80's claimed that gender was no longer a limiting factor in the art world, reviewed a show of American art in London for Time and said “You don't have to be a Guerrilla Girl to know that there weren't enough women in the show.” That's progress, even though Hughes reneged on a promise to apologize in this book for his past insensitivity.

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Mary Boone is too macho to admit we influenced her in any way, but she never represented any women until we targeted her.

Kathe Kollwitz: Museum curators feel compelled to suck up to us on camera. They used to ignore us and hope we'd just go away.

Gertrude Stein: The situation was pathetic. It had to change. And we were a part of that change.

Q. Has success ruined you?

33.3%: Yes.

33.3%: No.

The rest: Undecided.

Q. Where do you go from here?

All: Back to that jungle out there. Back to work.

Q. One last thing. How can you stand wearing those masks all day?

Emily Carr: It's hot.

Paula Modersohn-Becker: Not as hot as we make it out there.

Alma Thomas: But we look so beautiful, it's hard to complain.

Copyright ©1995 by Guerrilla Girls